The History of Onmyodo & Rumiko Takahashi's MAO

By Harley Acres

The Origins of Onmyodo

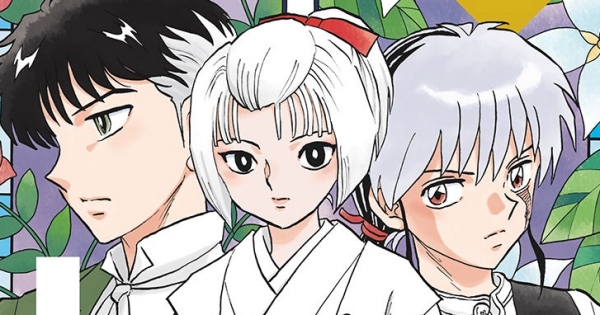

One of the core elements of Rumiko Takahashi’s 2019 manga MAO is its use of “onmyodo”. Onmyodo is a spiritual system of relationships between elements in nature and the way that they relate to one another. Sometimes onmyodo has been translated as “the art of yin and yang” and the practitioners, called onmyoji, as “yin-yang diviners”.

Takahashi has long incorporated elements of Japanese history and the supernatural together, and onmyodo is an ideal framework to build a compelling story around. Because of the philosophy’s esoteric nature its real-life historical use was multifaceted. Primarily onmyoji were the keepers and designers of the calendar, keeping track of when solar and lunar eclipses would take place, denoting auspicious or worrisome days when important events should occur or be avoided.

The more magical aspects frequently depicted in modern manga were also ascribed to onmyoji historically. From Noriko T. Reider’s book Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present the author writes:

"It was believed, in this period (the Engi-Tenryaku era of 901-947 CE), that the practitioners of onmyodo could use magic, and that some could see, and even create oni. Komatsu Kazuhiko writes that the foundation of the practitioners’ magical force is shikigami or invisible spirit. Using shikigami, the practitioners were actively involved in the lives of aristocrats. The onmyoji or yin-yang diviners used their magic at the request of their royal and aristocratic patrons and not infrequently against their patrons’ political enemies. Importantly, Tanaka Takako surmises that the shikigami that were left underneath the bridge—not just any bridge but Modoribashi Bridge in the capital—by practitioners of onmyodo such as Abe no Seimei, and eventually became various oni who stroll on certain nights in the capital." [1]

From a historical standpoint the concepts arrive in Japan from China during the Heian Period. It becomes insinuated into political life as famous onmyoji help to determine where the capital should be moved to. Eventually onmyodo falls into a decline as it is viewed with more skepticism over the centuries. By the 1800s it is treated as folklore and fortune-telling and little more. A law was passed in October of 1870 that formally abolished the onmyodo department within the government that set the calendar, kept track of astrological events, and managed the water clock.

Originally onmyodo was connected to the Chinese concept of yin and yang as well as the 5 Elements (fire, water, wood, metal and earth). The 5 Elements, known in Chinese as “Wuxing” were also associated with the 5 known planets at the time (Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). Each of the elements interacts with another in differing ways- generative or destructive. For instance:

- Wood serves as kindling for fire

- Fire creates earth (via lava)

- Earth contains metal

- Metal collects water vapor

- Water sustains trees, allowing wood to grow

That is how one element gives rise to another in a cyclical pattern. This aspect of onmyodo has not been addressed in MAO yet. Instead the manga tends to focus on the destructive or disruptive capacity of each element upon the other:

- Wood drains the earth of nutrients (there has not been an example of this particular interaction in MAO as of this article).

- Earth dams water (Nanoka versus the water creatures, or another interesting scene where Otoya explains how he was able to break a water seal on Hyakka’s hand due to his earth affiliation).

- Water extinguishes fire (Genbu a water creature defeating the mosquitos who are fire-associated as are all birds and flying insects).

- Fire warps metal (as we see in the battle between Hyakka and Hakubi).

- Metal harvests wood (Kamon would be weak against Hakubi should they battle) .

These elements, the wuxing, were connected to traditional medicinal techniques as well. The five elements were each connected to one of the five fingers on a hand, the five senses, five stages of life and five flavor profiles for food in addition to the five known planets. Consequently, it becomes easier to imagine how these concepts were all thought to be connected. Onmyodo could be used for healing as well as astrological predictions, casting curses, battling demons, and performing exorcisms. The wuxing concept of elements would later influence the Japanese concept of “godai” (五大). In godai the five elements are earth, water, and fire with wind and void replacing metal and wood.

This is but a brief primer on the basics of onmyodo. [2] I will also discuss the major historical onmyoji and how they fit into the story of MAO.

The Major Figures of Onmyodo

Historically there are two towering figures associated with onmyodo- Kamo no Yasunori (賀茂保憲) and Abe no Seimei (安倍晴明). I will primarily discuss how these figures connect with concepts in MAO rather than their historical lives.

Kamo no Yasunori, was said to have been able to visually see the demons presents during an exorcism when he was only ten years old. This is referenced in the initial test Mao and Daigo are given as children to see if they have the basic insight to begin their onmyodo training.

Abei no Seimei was Yasunori’s pupil. Born in 921 CE, he is directly mentioned in chapter 35 when Nanoka tells Shiraha that she thought he was a character from a video game when he helped her with her research on him. His “mon” or family crest is the pentagram, which is the five-pointed star used to denote the wuxing elements. We see this pentagram appropriated in the book and film-version of Doomed Megalopolis, where Yasunori Kato, the villain of the piece, has the pentagram on his gloves (it also helps give a sense of the forbidden taboo of its western connotations as well). The historical Abei no Seimei was also surprisingly long-lived for someone in the early 11th century. As a result, legends began to associate him with “Taizanfukun” (literally the “Lord of Mount Tai”) the guardian deity of one of the holiest mountain peaks in China. This figure, “Taizanfukun” became associated with the underworld and was placed in charge of writing names in the registers of life and death ), these Chinese Taoist beliefs became popular in Japan during the Heian Period (which is chronologically where the early portions of MAO take place). This is also the actual historical time of Abei no Seimei and the proliferation of onmyodo. From the Daoism Handbook by by Masuo Shinichiro (edited by Livia Cohen) and his discussions on Taishanfukun:

"Taishan (泰山), the sacred peak of the east, is located in Shandong (China) and was thought of as the residence of the dead. Its mountain lord Taishanfujun (泰上府君) served as the ruler of souls. It was central to imperial sacrifices and when the emperor made his ritual round throughout the country the sacred peak would be visited first. In Japan’s late Heian (11th-12th century), two further Daoist beliefs became popular in Japan: that of the Lord of Mount Tai (Jp. = Taizanfukun 泰山府君 or 太山府君), and that of the celestial administration of the underworld run by a multitude of hierarchically organized deities. Following ancient Chinese beliefs, the Lord of Mount Tai (Taizanfukun) was thought to reside in the sacred mountain of the east and serve as the ruler of fate, longevity, and good fortune, controlling the registers of life and death. He was a key subject for prayers for the avoidance of disasters and extension of life." [3]

Heian texts also mention other life-giving gods, including general officers such as the heavenly administrators, the departments of Earth and Water, the rulers of Fates and Emoluments, and the heads of the Six Departments, and specific deities such as the Northern Emperor, the gods of the Five Realms and the stars of the Northern Dipper. A total of twelve groups of gods were offered silk and coins and prayed to for support in life and the extension of longevity. Beyond this, special occasions, such as war, natural catastrophes, and epidemics, warranted further ceremonies of protection and avoidance of disaster. Again the Lord of Mount Tai served as one of the most efficacious deities, joined closely by the officials of the Department of Earth. These various rites and offerings, too, were conducted by esoteric monks who were also yin-yang diviners, following a complex mixture of medieval beliefs and practices that included a strong Daoist influence. One story of Abe no Seimei is particularly useful in illustrating the power of cursing and the reversal of a curse: From Naoko T. Reider:

"In a story that appears in Uji shūi monogatari (A Collection of Tales from Uji, ca. 13th century), old Seimei sees a handsome young chamberlain cursed by a crow-shaped genie. The genie is sent by an enemy yin and yang diviner and the young man’s life is in danger. “After sunset Seimei kept his arms tight around the chamberlain and laid protective spells. He spent the night in endless, unintelligible muttering.” Seimei’s protection is so strong that the genie is sent back to the enemy diviner and kills him instead." [4]

Another historical example that can be tied to MAO is from Chapter 52 when the hair and fingernails of enemies are provided for curses. In his book The Way of Yin and Yang: A Tradition Revived, Sold, Adopted Lee A. Butler writes:

"The emperor's annual observances were an eclectic mix, including festivals of song, dance, poetry, archery, planting, and harvest, as well as more weighty matters: indigenous purifications and exorcisms, Buddhist prayers and rituals, and various "Confucian" practices, of which some can be classified as onmyodo. Among the onmyodo-based observances were hagatame, susuharai, and migushiage. The first, hagatame, entailed feasting on certain foods- rice cakes, radishes, venison, melons, and so on-for the purpose of receiving strength and long life; the second, susuharai, was the literal cleaning of a person's residence in the Twelfth Month in preparation for the new year; the third, migushiage, was the ceremonial burning of cut fingernails and toenails, hair lost from the head, and hair-ties used during the year. The origins of all three practices are obscure; in fact, it is likely that their link to onmyodo came rather late historically. Nonetheless, they became part of onmyodo's domain because they had to be carried out on auspicious days, divined by the Bureau of Yin and Yang's onmyoji. And they were practices that were revived in the reunification era." [5]

The Doomed Megalopolis Connection

Perhaps no novel has done more to revive the idea of onmyodo in popular culture than Hiroshi Aramata's novel Teito Monogatari (The Tale of the Imperial Capital) or as it is known in the West, Doomed Megalopolis. [6] The novel has been adapted into live-action films and anime and focuses on one of modern Japan's greatest horror characters, Yasunori Kato. Kato is an incredibly powerful onmyoji seeking to bring about the ruin of Japan by manipulating world events. The excitement of the series comes from the way real life historical characters are brought it to battle or become manipulated by Kato. Much as the Indiana Jones films use World War II and Nazi as a setting for their stories, Doomed Megalopolis mines the interwar years of the 1920s and 1930s in Japan with particular skill.

Japanese oni are often used as representative of “the other”, or the outsider. In Nariko T. Reider’s book Japanese Demon Lore she discusses how oni are viewed as outside of the power of the Emperor’s influence. Consequently during more nationalistic eras the enemies of the Emperor were associated with oni, whether that include Roosevelt and Churchill during World War II or earlier rebels against the Imperial Family such as Emperor Sutoku who was exiled and was said to have held a grudge transforming him into an evil spirit bent on revenge. [7] Though Emperor Sutoku was overthrown in 1156 CE the grudge it was believed he embodied was still so present in Japanese culture that upon his enthronement in 1867 Emperor Meiji invited Sutoku’s spirit to his inauguration in an attempt to placate the 700 year old spirit.

Similarly the story of Doomed Megalopolis involves another historical figure- Taira no Masakado who, like Emperor Sutoku, revolted against the Emperor and declared the position for himself before he was captured and killed in 940 CE. In Doomed Megalopolis it is his spirit that has become both a protector of Tokyo, but if aroused, a destroyer much in the same way Godzilla is shown to have a dual nature as both good and evil. In the story the wicked Yasunori Kato is trying to rouse Masakado’s spirit and carry on his war against the Imperial Family and the capital itself- Tokyo.

The Rise and Fall of Onmyodo

Though it is vague, there is a feeling in MAO that the Goko Clan in which Mao and his fellow onmyoji are members has fallen out of favor. There are cryptic mentions that certain arts are now taboo and that the Master of the Temple grouses at the restrictions his order has been placed under. It is clear from his bloodthirsty and cruel manipulations of MAO and his fellow pupils that he chafes under the yolk of his unseen imperial overseers.

It is difficult to place the setting of the early portion of MAO in a particular year. It has been said to be the Heian Period (794-1185 CE), a wide range of dates that covers centuries. In chapter 14, set in the 1920s, Mao states that he is approximately 900 years old, making his time of birth and the beginning of the story sometime around the early 1000s CE, approximately three-quarters into the Heian Period. By this point in time onmyodo had risen to prominence but also been cast aside by some Emperors. In the research journal Monumenta Nipponica Vol. 51 No. 2 from summer 1996, Lee A. Butler writes about onmyodo...

"Onmyodo's path from the seventh century to the Sengoku era was neither straight nor smooth. Like other ideas and institutions adopted from the Chinese, onmyodo had an immediate appeal while being reviled by those with a stake in competing interests. In this instance the primary competition came from the powerful Ministry of Kami Affairs, or jingikan (神祇官) to which the Bureau of Yin and Yang remained subordinate through the early part of the Heian period. The Bureau of Yin and Yang scored occasional victories, seen in requests to conduct prayers for rain or to perform ceremonies against malicious spirits (物の怪/mono no ke) at the palace. But these were few in number. The weakness of the Bureau is apparent in the officials who occupied it; they were low-ranking courtiers, often men recalled from the countryside to fill undesirable positions. A gradual shift began as the Fujiwara rose to power. Fujiwara clan members of limited status came to dominate the Bureau, and in time its influence surpassed that of the Ministry of Kami Affairs. Even so, not all were enamored of the Bureau's workings. Emperors Saga (reign 809-823), and Junna, (reign 823-833), expressed their disdain of onmyodo practices in general, and an edict of Saga in 810 attacked directional taboos, calendrical taboos, and the like. Saga's feelings were so strong that in his last will he ordered that no onmyodo activities be performed in conjunction with his death, because, as he stated, he had no belief in their efficacy. These instructions were followed until the death of Emperor Junna in 840, after which onmyodo was rapidly revived. Within a few years, anniversary celebrations of Saga's death were being conducted on auspicious days, in direct opposition to his orders." [8]

Onmyodo had further declined during the disruption of the Warring States Era, the Sengoku Period (1467-1615 CE). Because of the elaborate ceremonies and time required to perform them, it was simply not practical to conduct them when the country had broken down into a state of civil unrest. During this time onmyodo became more martial in nature- when it was used sparingly it was to give auspicious days for battles to occur or directions from which to attack. Building the calendar, predicting eclipses and suggesting imperial residences were skills that were used intermittently and intergenerational knowledge of these skills became fragmentary.

By the late 1400s and early 1500s onmyodo was rarely used and the two great families, the Tsuchimikado and the Kamo had dwindled to shadows of their former significance. The Tsuchimikado had all left Kyoto, then the capital, and settled in Wakasa where they performed their onmyodo skills for merchants by telling them auspicious directions for their shops to face. The Kamo line who still serviced the imperial court died heirless in 1492 and one of the Tsuchimikado was called upon to fulfill the duties of building the calendar (a process that had been in the care of the onmyoji for centuries). The Tsuchimikado family’s skills had deteriorated to such an extent that the predicted days for solar and lunar eclipses in 1586 failed to be met causing great embarrassment for them.

These historical declines are alluded to in MAO as the Goko Clan becomes unravelled, their secret skills stolen and scattered to the winds, only for the militant Hakubi (clearly based upon Doomed Megalopolis' Yasunori Kato) begins to manipulate and plot with designs on reviving the powerful clan during the 1920s.

Footnotes

- [1] Reider, Noriko T. Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present, 14. University Press of Colorado, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgpqc.7.

- [2] Acres, Harley & Dylan Acres. "Onmyodo - MAO Online." Rumic World. October 9, 2022. https://www.furinkan.com/mao/ culture/references/onmyodo.html.

- [3] Shinichiro, Masuo., Livia Kohn. "Daoism in Japan," Daoism Handbook, 821. Brill, 2000.

- [4] Reider, Noriko T. Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present, 16. University Press of Colorado, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgpqc.7.

- [5] Butler, Lee A. "The Way of Yin and Yang. A Tradition Revived, Sold, Adopted." Monumenta Nipponica Volume 51 Number 2, 189-217. Sophia University, 1996. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2385087.

- [6] Hiroshi Aramata's Teito Monogatari (帝都物語, literally The Tale of the Imperial Capital) is a twelve volume series of novels published between 1985-1989. The series won the 1987 Nihon SF Taisho Award (日本SF大賞). Other winners include Katsuhiro Otomo's Domu, Otherworld Barbara (バルバラ異界) by Moto Hagio and Mamoru Oshii's Ghost in the Shell sequel Innocence (イノセンス).

- [7] Reider, Noriko T. Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present, 104-119. University Press of Colorado, 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt4cgpqc.12.

- [8] Butler, Lee A. "The Way of Yin and Yang. A Tradition Revived, Sold, Adopted." Monumenta Nipponica Volume 51 Number 2, 189-217. Sophia University, 1996. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2385087.

For more video content on MAO from Harley Acres, you can watch "MAO's Historical Connections" and "The Dark Magic of the 1920s - MAO & Doomed Megalopolis". You can also see our MAO YouTube playlist for a constantly curated selection of videos on the topic.

Rumic World

|