Kazuhiro Fujita X Ryoji Minagawa

Because Takahashi-sensei was there, we can draw manga.

Translated by: Harley Acres

The two friends, who both debuted in 1988 and are still at the forefront of shonen manga, passionately talk about their great predecessors who have paved a new path in Sunday!

Everyone was in love with Lum.

Ryoji Minagawa: I've been reading Takahashi-sensei's works in real time since the early days, and the first thing that hooked me was how good her "conversations" are. Of course, those exquisite conversations, both in tempo and content, is unique to manga, but I tried to see if I could have the same conversation with people in real life (laughs). However, I thought I was the only one who was into Takahashi-sensei's works, but it turned out that all the manga fans of my generation were fascinated by that type of conversation. In any case, when I think of Takahashi-sensei, of course her drawings and characters are wonderful, but the first thing that comes to mind for me is her "conversational rhythm."

Kazuhiro Fujita: When I was a teenager, I surely would have liked to talk with girls the way her characters do (laughs). But Minagawa-kun, you aren't particularly influenced by Takahashi-sensei in terms of your art style, are you?

Minagawa: No, not particularly.

Fujita: Yeah, right. I think of your style as being more influenced by Wild 7's Mikiya Mochizuki-sensei , Katsuhiro Otomo-sensei, or someone like that. [1]

Minagawa: Of course, both of them had a big influence on me, but when I was in high school, I admired Takahashi-sensei's drawings and I'd always imitate them. I didn't think my drawings looked like hers at all, but my classmate, Masaomi Kanzaki-kun, complimented me (laughs). [2] Also, when I started drawing manga, I only drew studies that looked like degraded copies of Takahashi-sensei's work. In short, Takahashi-sensei is "the person who changed my world." So, for example, the work Urusei Yatsura which I fell in love with way back then, was as important to me as Star Wars when I was a teenager. [3] I've never said this out loud until now. I know, you've openly stated that you were influenced by Takahashi-sensei in various interviews, Fujita-kun.

Fujita: Yes, I definitely am. Because I love her work. I'd like to see the Takahashi-sensei-style manga that you drew in high school, but then again, so did I. I first fell in love with Takahashi-sensei's manga when I was in high school. Of course I loved Urusei, but I was really shocked by her horror stories like When My Eyes Got Wings, The Laughing Target, and Sleep and Forget. I thought, "Wow, how can there be manga like this?" (laughs). [4]

Minagawa: That's great (laughs).

Fujita: Well, yes, I really thought that (laughs), I mean, I was so shocked that I couldn't make a proper judgment. Also, from a pictorial point of view, my drawings of girl characters are definitely influenced by the heroines that Takahashi-sensei draws. When it comes to beautiful girls, Rumiko Takahashi and Fujihiko Hosono are my favorites. Until then, I had never read manga for the artwork, but the girls in their manga were especially cute. [5]

Minagawa: I also really respect Hosono-sensei. It's true that that your beautiful girls are reminiscent of the look and lines of the heroines drawn by the two of them, Fujita-kun.

Fujita: It's in my blood. I spent a long time studying the balance between the head, torso, and legs of the girls that Takahashi-sensei draws (laughs). Hosono-sensei's girls are long from the shins down, but Takahashi-sensei's girls from the early days are short.

Minagawa: Takahashi-sensei's drawings of girls are not realistic, but have proportions that appeal to men as "manga drawings." They're wonderful. I can't tell you how many times I copied the picture of Lum on the cover of the second volume of Urusei Yatsura (laughs).

Fujita: I can't compete with Takahashi-sensei, who is a woman afterall, when it comes to making drawings with those "proportions that appeal to men" (laughs).

Minagawa: All middle school and high school boys of that era must have been in love with Lum-chan.

Fujita: I agree. Everyone was in love with Lum-chan, and to be extreme, I think that since Takahashi-sensei's debut, boys have been learning about the ideal girl from her manga. I feel like Japanese boys are simulating the process of meeting a girl they like, dating, and getting married by reading her work.

Minagawa: I wonder what kind of attitude a man should have to make a girl feel jealous (laughs).

Her lines don't keep people apart.

Fujita: And, without fear of being misunderstood, Takahashi-sensei's drawings are good in that they can be imitated if one tries hard enough. Of course, her drawings are one-of-a-kind, and no one else could possibly draw them, but I feel that her use of lines doesn't keep people apart from her.

Fujita: And, without fear of being misunderstood, Takahashi-sensei's drawings are good in that they can be imitated if one tries hard enough. Of course, her drawings are one-of-a-kind, and no one else could possibly draw them, but I feel that her use of lines doesn't keep people apart from her.

Minagawa: I like that phrase "lines don't keep people apart". But I understand what you mean. The 70's saw the rise of gekiga and the 80's saw the breakthrough of Otomo-sensei, and while the taste of the times was inevitably moving in the direction of realism, I think it is amazing that she dared to maintain her own unique line of manga imagery while establishing an era. [6]

Fujita: Come to think of it, when I started bringing in manga submissions around the age of 20, my editor used to tell me that all the newcomers at that time were only submitting manga that looked like copies of Otomo, Akira Toriyama, or Takahashi. [7] So I started thinking that I had to step away from that, but I can understand the desire to imitate them (laughs).

Minagawa: Actually, I used to draw things like that too, so I'm in no position to say anything (laughs).

Fujita: I'm the same way. Dreaming of a girl falling from the sky or suddenly being forced to live with a mysterious beautiful girl, these are all scenarios that come from under the influence of Takahashi-sensei.

Minagawa: Indeed, if you look at the extra issues of Shonen Sunday that collected newcomers' works, they were all those kinds of manga. I think it's great that you made a conscious decision to move away from that sort of thing.

Fujita: Well, what I turned away from was the romantic comedy represented by Urusei and Maison, and as you can see from my debut work Strange Fairy Tale (連絡船奇譚/Renrakusen Kitan), I was greatly influenced by short stories such as When My Eyes Got Wings. I've said this in various places in the past, but the way Takahashi-sensei depicted the development of "an ordinary human being overcoming the supernatural" in her short stories was truly mind-blowing. I think there have been stories like this in novels, but this was the first time I saw it in a manga.

Minagawa: I was reading some of Takahashi-sensei's works before coming here today, and all of them are amazing.

Fujita: She has a lot of violent stories (laughs). Minagawa-kun, which works do you particularly like?

Minagawa: Like you, Fujita-kun, I think the best one-shot is When My Eyes Got Wings.

Fujita: Indeed, that one's the best. However, as Takahashi-sensei said before, many readers were confused about the series of horror one-shots she did at the beginning of her career. As you mentioned, Minagawa-kun, the image of Urusei is so strong that even if she writes a serious work, the reader seems to be reading it expecting a gag to come on the next page.

Minagawa: Right (laughs). However, as she continued to publish several horror one-shots, everyone soon came to understand that she was a person who could do both gags and serious stories. Admittedly, it may have been confusing at first.

The manga she's currently drawing is incredibly amazing.

Fujita: What's her best major work, do you think?

Minagawa: I like them all, but if I had to choose, it would be Urusei Yatsura. As I said earlier, reading that book changed the world in front of me. Ranma is also a little hard to toss out of the picture, though. When I saw that she was able to hit the mark again immediately after a hit work like Urusei without any hesitation, I thought that she was really amazing (laughs).

Fujita: Ranma was written around the time of our debut, so it was even more shocking.

Minagawa: Fujita-kun's favorite is definitely Inuyasha.

Fujita: Yes, it is. Of course the story was interesting, but I was also happy that Takahashi-sensei came so close to my genre (laughs). I thought to myself, "Takahashi-sensei, whom I have the utmost respect for, has finally drawn a manga about yokai!" (laughs). In that sense, I also loved the Mermaid Saga, but I vaguely thought of it as not one of Takahashi-sensei's mainstream works. But Inuyasha certainly was one of her main series, so I was very happy to see it. Come to think of it, isn't MAO, the series she's working on now, also along those lines?

Minagawa: That's right.

Fujita: I hate how interesting it is!

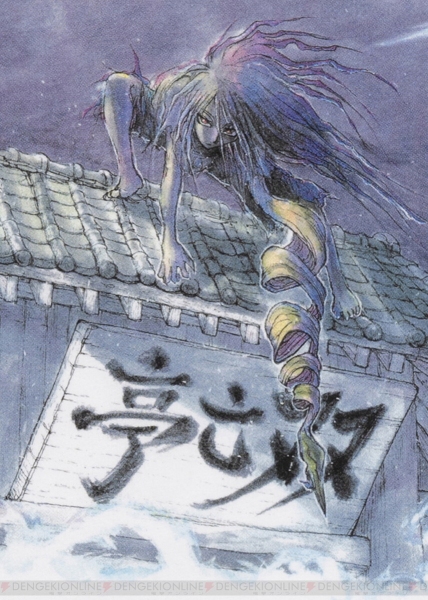

Minagawa: I really look forward to reading MAO every week. I guess she's trying to make the series more interesting and exciting, but I was thrilled to see that after Kyokai no RINNE, which was generally very warm and relaxed, that now she's working on a dark fantasy story like this.

Fujita: Don't you feel that MAO is written in a slightly different way than Takahashi-sensei's previous works?

Minagawa: It seems a little slow so far. Though not in a bad way.

Fujita: Yes, I think Takahashi-sensei usually flies along at a swifter pace. That unhurried feel may be similar to the tempo of a modern horror novel. But the tempo is also comfortable to read. I feel like she's doing what she wants to do and breathing the way she wants to, and I admire that aspect of her as well.

Minagawa: Having a cool main character with a scar on his face is something I haven't seen before, but the heroine, Nanoka, is also great.

Fujita: She also seems to have some mysterious power, but I like that Nanoka is not a heroine in the sense of being an obvious heroine, but rather she comes off as an ordinary person.

Minagawa: Perhaps that ordinary person's perspective will be utilized in the future.

Fujita: So, getting back to what I think is Takahashi-sensei's best major work, well isn't MAO just beginning? In that sense, I feel like it will be the best major series by the time it's finished. I guess I'll decide that Inuyasha is the tentative best for today (laughs).

Minagawa: That's sneaky (laughs). So I'm going to choose Urusei as my tentative best. It all depends on what happens with MAO. But either way, we always want our readers to think, "The manga we're currently drawing is the best."

Pioneering the lighter fare of Sunday in the 80s.

Minagawa: It's often said "How is it that a woman, Takahashi-sensei, can portray the feelings of young men so realistically?", but Takahashi-sensei realistically depicts the feelings of not only young men, but all people, young and old, male and female. That's what's so amazing.

Fujita: Come to think of it, my wife said the same thing. In Takahashi-sensei's manga, the relationship between wives and their mothers-in-law is so realistic that it's scary (laughs). [8]

Minagawa: That's probably what everyone is thinking, from an old man on the verge of retirement to a middle school girl. Maybe Takahashi-sensei has a flexible brain, or rather she just accepts all types with gusto.

Fujita: She's very different from me, who stubbornly rejects all sorts of things.

Minagawa: That's a good thing about you, don't ever change (laughs).

Fujita: Aesthetics and aesthetic sensibility may sound cool to discuss, but everyone has them to a greater or lesser extent, don't they? What is great about Takahashi-sensei is that while she has a solid aesthetic, she has the capacity to accept anything and everything without limitation within her sensibility.

Minagawa: I really think so. Everyone calls Osamu Tezuka-sensei the "God of Manga," but perhaps you could call Takahashi-sensei the "Mother of Manga." I think she is such an inclusive and warm-hearted mangaka.

Fujita: I know exactly what you mean to say, however I can't call Takahashi-sensei "mom" (laughs), so I'll just call her "Goddess of Manga". I guess there are still many things that she still wants to draw. That's why she shows a different face every time she's serialized.

Minagawa: Well, I guess I'll have to try writing a romantic comedy next time.

Fujita: Definitely draw that. I want to read a Ryoji Minagawa romantic comedy.

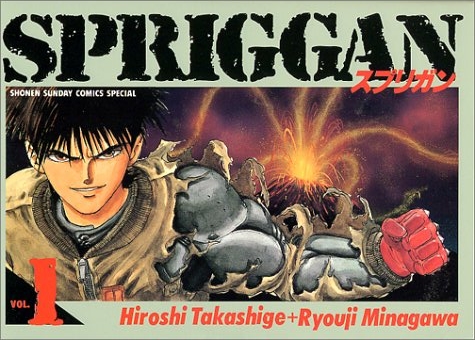

Minagawa: I was originally copying Urusei, so when I debuted, I actually wanted to make a romantic comedy. I think I could have gone in that direction back in the days of my debut work (HEAVEN), but now I'm too strongly associated as the guy who made Spriggan and Project: ARMS, so it's hard to go back to that side. It's gone (lol). Come to think of it, you're probably like that too. You used to want to draw girls' manga, right? [9]

Fujita: I still want to draw it, it's not just something I used to love. But, looking at Takahashi-sensei, who is always challenging herself to do various things with each new series, she draws what she wants without worrying.

Also, speaking of Takahashi-sensei, don't you get the impression that she was the one who opened a new path for Shonen Sunday, which had been dominated by dark, masculine manga before she came along?

Minagawa: Yes, she and Mitsuru Adachi-sensei. [10]

Fujita: Yeah, yeah. Takahashi-sensei and Adachi-sensei created the image of Sunday in the 1980s. They were the ones who portrayed the reality of that era, when men didn't just spend all their time fighting or putting their lives on the line for sports, they also wanted a girlfriend. Not only that, but I think it's because of that lighter route they paved that the two of us and the slightly quirky manga that we are known for stood out more (laughs).

Minagawa: I agree. We're the mavericks of Sunday (laughs). However, I think it's amazing that the lighter path paved by Takahashi-sensei and Adachi-sensei is still being continued in Sunday.

The first time we met.

Do you remember the first time you met her?

Minagawa: I remember well. When I actually saw her for the first time, the first thing I thought was, "Wow, Rumiko Takahashi actually exists" (laughs). As I said earlier, Takahashi-sensei is the person who introduced me to the world of manga. I also liked Mikiya Mochizuki-sensei when I was a child, but manga and manga artists were from some faraway land to me. But when I was looking at Urusei Yatsura, I felt the message beaming out from the pages: "If you want to draw, then you should draw, too." That's why Takahashi-sensei changed my life. There was no way she could say anything even if I had confessed all this right in front of her, so I just stared at her from a distance for a while (laughs).

Minagawa: I remember well. When I actually saw her for the first time, the first thing I thought was, "Wow, Rumiko Takahashi actually exists" (laughs). As I said earlier, Takahashi-sensei is the person who introduced me to the world of manga. I also liked Mikiya Mochizuki-sensei when I was a child, but manga and manga artists were from some faraway land to me. But when I was looking at Urusei Yatsura, I felt the message beaming out from the pages: "If you want to draw, then you should draw, too." That's why Takahashi-sensei changed my life. There was no way she could say anything even if I had confessed all this right in front of her, so I just stared at her from a distance for a while (laughs).

Fujita: I know that feeling (laughs). When I first met her, I was really nervous and asked her, "What are your hobbies?" Then Takahashi-sensei suddenly smiled and said, "I wonder if there's anything interesting besides manga..."

Minagawa: That's too cool (laughs). I was so scared that I couldn't say anything straight. A while later, there was a gathering of young manga artists on a houseboat, and that's when we finally got to talk a little bit. [11]

Fujita: I remember the houseboat. By the way, did you know that I was the one who invited Takahashi-sensei?

Minagawa: Oh, that's right. What the heck, great job.

Fujita: I agree. It wasn't just me, but all the young mangaka must have wanted to talk to Takahashi-sensei, so I asked her to come despite her busy schedule. By the way, what did you talk about?

Minagawa: I asked about how Maison Ikkoku has 15 volumes, and did she decide on the direction of the story from the beginning?

Fujita: That's a good question from a young mangaka.

Minagawa: Then, she said she had decided on the last scene but the rest of the story was improvised chapter by chapter. This may be common sense for a serialized manga, but I'm the type of person who can't draw a manga until the detailed structure of the whole story has been settled on, so I feel a little better knowing that there is a way to draw a manga like that.

Fujita: That might mean that her characters move on their own.

Minagawa: That's right. I knew in my head that characterization was more important than anything else in manga, but it wasn't until after I became a professional that I truly understood it. I had several opportunities to go out to eat with her after that, but I still got nervous and couldn't speak well. I wasn't like you and asking her about her hobbies. I could only say things like, "This is delicious," or other such unimportant things (laughs).

To draw the best manga.

Fujita: For me, the biggest purpose of manga is to make people happy. To achieve this, the first step is to draw manga that are easy to understand and to give the reader a good feeling. I think the best manga are those that do this properly. In other words, in my opinion, manga is not something that makes readers feel bad. Of course, it would be nice if there were manga like that as well, but that's not my ideal manga, and the person who continues to draw my ideal manga is Rumiko Takahashi. That's why I've often said that "Takahashi-sensei is the strongest manga artist." And I believe that the greatest weapon for drawing the strongest manga is those unique approach. [12]

Minagawa: If you combine the best parts of gekiga and the best parts of traditional manga and simplify them further, you might get something like that. It's not something that can be easily imitated, though.

Fujita: I want to imitate that style. But those warm, exquisite lines are hard to imitate even if you want to. I can't really describe it, but I like the feeling of intentionally stopping just before it becomes beautiful and sharp. That may be the secret to having warm lines instead of cool lines. That's what I meant when I said earlier that "her lines don't keep people apart." Also, there's all kinds of pictorial information to take into account, such as the area of the blank space within the panels, is concentrated in an easy-to-understand manner.

Minagawa: I really admire Takahashi-sensei's easy-to-understand manga. At the beginning of this conversation, I said that Takahashi-sensei's very good at dialogue, but she also really considers how to make the reader feel comfortable. Even though I can't do the same thing, I'd like to get a little closer. Mangaka like me want to put everything we can into each panel, but I think it's also important to cut out unnecessary things in order to create the form that's easiest for the reader to see. I've learned something in thinking about that.

In my case, as I said earlier, when I was in high school, I liked Takahashi-sensei's manga and copied her, and Kanzaki-kun praised my work and we became good friends. If you think about it, you can say that Takahashi-sensei is a benefactor who indirectly paved the way for me to become a mangaka. [13] That's why Rumiko Takahashi has been an indescribable mentor in my life. She taught me about the rewarding and wonderful world of making a living by drawing manga.

Fujita: I can say the same thing too. Also, when I think about it now, it's a minor thing, but I remember having some bad experiences when I was in high school. But when I went home and flipped through Takahashi-sensei's manga, I was able to completely forget about those things. Now that I'm a professional, I'm always asking myself, "Am I able to draw a manga that can do that?"

Minagawa: That sort of feeling is important.

Fujita: When you think about how many people have become manga fans through the gateway of Takahashi-sensei's, it's truly amazing. Some of them, like Minagawa-kun and myself, have even become professional mangaka.

Sunday wouldn't be Sunday without Takahashi-sensei.

Editorial Department: It looks like both of you haven't fully finished talking about your passionate love for Rumiko Takahashi (laughs), but unfortunately our time is almost up, so in closing, please give a message to Takahashi-sensei.

Minagawa: Actually, I've always wanted to say directly to her, "Thanks to you, I'm living a happy life as a manga artist," but I'm too nervous. I hope I can say that to her someday though. Also, I've been really thinking lately that Sunday without Takahashi-sensei isn't Sunday at all.

Fujita: Ryoji Minagawa-sensei said it best. I can't think of a better phrase than that. But that's exactly what it is. Sunday without Takahashi-sensei isn't Sunday at all, and I wonder how much Takahashi-sensei's manga has saved us. I think the only way to repay that favor is to draw interesting manga ourselves.

Minagawa: Fujita-kun is still struggling alone in Sunday, and I respect him just as much.

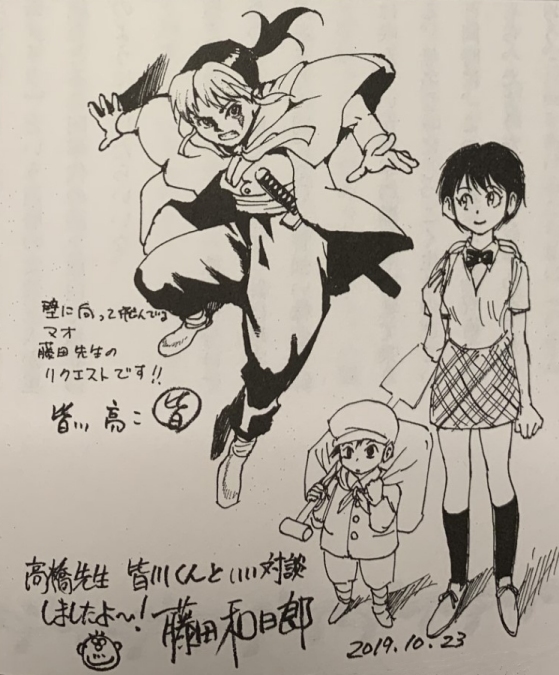

Fujita: Thank you. Well, you should come back too (laughs). Even now, I still think about it sometimes. When we debuted at the same time, we sat next to each other with flowers held to our chest at the Newcomers Manga Award ceremony. [14] You and I have been friends since then, so just thinking that Ryoji Minagawa is in the same world still cheers me up. And from what I've heard today, in a sense, it was Takahashi-sensei who created this opportunity for us, in other words, we are all indebted to Takahashi Sensei in every way. I can't thank you enough for that.

Kazuhiro Fujita, Mangaka. Debuted in 1988 with Strange Fairy Tale (連絡船奇譚/Renrakusen Kitan). His representative works include Ushio & Tora (うしおととら) and Karakuri Circus (からくりサーカス). His latest work is Sobotei Must Be Destroyed (双亡亭壊すべし/Sobotei Kowasubeshi).

Ryoji Minagawa, Mangaka. Debuted in 1988 with HEAVEN. His representative works include Spriggan and Project ARMS. His latest work is Dante the Sea King (海王ダンテ/Umi-oh Dante).

Footnotes

- [1] Wild 7 (ワイルド7) was a popular 1969-1979 manga series that ran in Shonen King by mangaka Mikiya Mochizuki (望月三起也). The manga was popular for interweaving the timely student protest movement into the story. Rumiko Takahashi mentions being a fan of the series in an interview. Katsuhiro Otomo (大友克洋) is one of the most noted mangaka and film directors. He created AKIRA, Domu (童夢), Fire-Ball, Sayonara Nippon (さよならにっぽん) and many short stories. He has directed anime films including adapting his own manga AKIRA, Steamboy (スチームボーイ) and the live-action film Mushishi (蟲師). Otomo is often cited as the main figure within the New Wave. The New Wave (ニューウェーブ) movement in manga is a product of the late 1970s into the early 1980s characterized by experimental works that did not fit into the traditional shonen/shojo/seinen/adult manga categories that were established at the time. Small circulation manga magazines such as June (ジュネ), Peke, Boys and Girls Complete Competitive Collection of SF Manga (少年少女SFマンガ競作大全集) and Supplemental Volume of Fantastic Sci-Fi Manga Complete Works (別冊奇想天外SFマンガ大全集) were the homes of these experimental newcomer manga artists. Katsuhiro Otomo (大友克洋) and Hideo Azuma (吾妻ひでお) are both held up as universally agreed upon members of the New Wave, though there is little overall consensus. Other artists often cited as part of the New Wave include Jun Ishikawa (いしかわじゅん), Daijiro Morohoshi (諸星大二郎), Hiroshi Masumura (ますむらひろし), Noma Sabea (さべあのま) and Michio Hisauchi (ひさうちみちお). Though Rumiko Takahashi is not often named as a part of the New Wave, I feel a case could be made to include her. She is of the era and published some small works in Boys and Girls Complete Competitive Collection of SF Manga such as ElFairy/Sprite. The New Wave is said to have ended with the launch of Big Comic Spirits and Young Magazine which served as more mainstream homes for these avant garde artists. Rumiko Takahashi, Hideo Azuma and Jun Ishikawa all were published in the first issues of Big Comic Spirits.

- [2] Masaomi Kanzaki (神崎将臣) is the artist and writer on the early 1990s manga adaptation of Street Fighter II. His other work includes Hagane (鋼) and XENON-199X・R-.

- [3] Kazushi Shimada (島田一志) interviewed Rumiko Takahashi and made a similar point that Star Wars debuted in Japan in 1978, the same year she made her debut, and he often makes this association between them.

- [4] While being interviewed on Naoki Urusawa's Manben television program, Kazuhiro Fujita goes as far as saying that When My Eyes Got Wings is the single story that proved to him he could make the style of manga he wanted to. He has continually found success in the horror/action genre with series such as Ushio & Tora (うしおととら), Karakuri Circus (からくりサーカス), and The Black Museum: Ghost and Lady (黒博物館 ゴースト アンド レデ).

- [5] Fujihiko Hosono (細野不二彦) is a fellow alum of Shonen Sunday known for Crusher Joe (クラッシャージョウ), Gu Gu Ganmo (Gu-Guガンモ), Gallery Fake (ギャラリーフェイク) and Dokkiri Doctor (どっきりドクター).

- [6] Takahashi was asked if she ever felt the need to copy Katsuhiro Otomo's style in the early 1980s when so many other mangaka were taking their cues from him.

- [7] Akira Toriyama's (鳥山明) is the creator of Dr. Slump (Dr.スランプ) and Dragon Ball (ドラゴンボール) and was publishing in Shonen Jump throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Along with his manga work he also did character designs for the Dragon Quest series of video games and Chrono Trigger.

- [8] Though not mentioned by name here, Takahashi stories with a strong wife/mother-in-law plot element includes Hidden in the Pottery, A Dutiful Vacation and Extra-Large Size Happiness.

- [9] Ryoji Minagawa (皆川亮二) debuted in 1988 with HEAVEN. From 1989 to 1996 he illustrated Spriggan (スプリガン) alongside writer Hiroshi Takashige (たかしげ宙). Spriggan was a fairly early manga that was partially published by Viz in English in the 1990s, who had retitled it as Striker. Though Viz did not publish the entire series, Seven Seas published the complete series under its original title to completion from 2022-2023. Minagawa's other manga includes Project ARMS (also published by Viz in English) and D-LIVE!!.

- [10] Mitsuru Adachi got his start in shojo comics before moving to Shonen Sunday which would be his primary publisher for the vast majority of his career. At Sunday he published alongside Rumiko Takahashi for three decades before he moved to Gessan, the monthly Sunday imprint. Adachi is well known for his romantic sports comedies such as Touch, Miyuki, H2, Katsu and Mix among many, many others. You can read a very early interview between Takahashi and Adachi here.

- [11] This same houseboat party is discussed by Rumiko Takahashi and Takashi Shiina in a 2022 interview.

- [12] Takahashi has mentioned this before, explaining that she does not want to make people feel bad while reading her manga. "I didn't want to draw a manga that people would feel bad about reading, and I dared to take the story in a more silly, more cheerful direction."

- [13] Ryoji Minagawa made his professional debut after working as Masaomi Kanzaki's assistant.

- [14] Fujita is discussing the Shogakukan Newcombers Manga Award, which he and Ryoji Minagawa both won in its 22nd interation. Takahashi won honorable mention for the 2nd Shogakukan Newcomers Manga Award (第2回小学館新人コミック大賞) in the shonen category. The way the Newcomer Manga Award is structured is there is a single winner and then two to three honorable mentions that are unranked. In 1978 the winner in the shonen category was Yoshimi Yoshimaro (吉見嘉麿) for D-1 which was published in Shonen Sunday 1978 Vol. 26. The other honorable mentions in addition to Rumiko Takahashi were Masao Kunitoshi (国俊昌生) for The Memoirs of Dr. Watson (ワトソン博士回顧録) which was published in Shonen Sunday 1978 Vol. 27 and Hiroaki Oka (岡広秋) for Confrontation on the Snowy Mountains (雪山の対決) which was published in a special edition of Shonen Sunday (週刊少年サンデー増刊号). Oka would also publish later under the name Jun Hayami (早見純). Other winners in various Newcomers categories include Gosho Aoyama, Koji Kumeta, Yuu Watase, Kazuhiko Shimamoto, Naoki Urasawa, Yellow Tanabe and Takashi Iwashige.

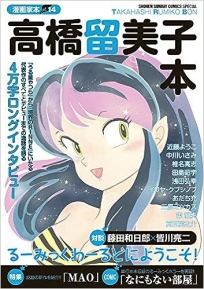

漫画家本 Vol.14 高橋留美子本

|