Festival d'Angoulême Interview

Translation by: Antoine Roizer

Takahashi: I had two elder brothers, and we often played outside together. But above all, I loved drawing. I felt like it was the only thing I did. My father was an independent physician, and on the medecine bags he gave to his patients, he drew kappa. [1]

He made this kind of drawing, and thus I tried to mimic those he gave me. Those were very simple drawings, almost drawn with only one stroke. They were easy to understand for children, that kind of drawing. My brothers bought manga, and as there were many of them at home, I read them. Fujio Akatsuka, Fujio Fujiko or Osamu Tezuka's were the first ones I loved. [2] At the time, I had the feeling that cartoons were something we watched in theaters. As for me, I mainly read manga, and those by Osamu Tezuka were the most plentiful.

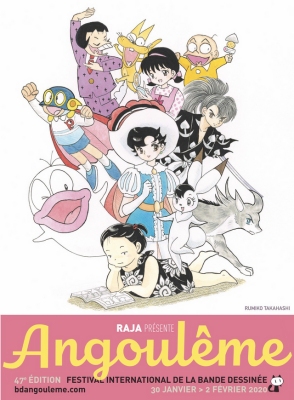

On the Festival's poster, I put several characters from the manga Osomatsu-kun by Fujio Akatsuka. I often copied his drawings. In fact, I often mimicked the artists I liked.

It's often said that your favorite mangaka are Shinji Mizushima and Ryoichi Ikegami. How did you discover them? [3]

Takahashi: When I was a child, I started reading Weekly Shonen Sunday, where Fujio Akatsuka, Fujiko Fujio or even Osamu Tezuka were published. It's within those pages that I discovered Shinji Mizushima, when he joined the magazine. Thus I started reading Ryoichi Ikegami and Shinji Mizushima a little later, when I was roughly ten.I discovered Ryoichi Ikegami in Garo magazine. A copy laid around in the waiting room of an ear, nose and throat doctor's office, and leafing through it, I was impressed by Ryoichi Ikegami's work. At the time when I started reading his manga, his drawings seemed, how to say... For example, when he draws women, their skin seems so soft, but it's only a pencil drawing. The skin texture was beautiful... The stories were absurd, but I was charmed by his drawings.

That's because I wanted to read Ryoichi Ikegami's manga that I bought Garo. [4] And in Garo, of course, Yoshiharu Tsuge was... great. Even outside Garo, everyone knew him. [5] When I was in junior high and in high school, Go Nagai drew manga belonging to very different genres. [6] But he always kept his style, the Go Nagai style, that was to be found as much in his comedic stories as in his more serious work. That was a quality I admired. I too aspired to become a cartoonist that would be able, with a unique style, to touch on any genre.

The manga I drew just after elementary school and those from my professional debut are obviously very different. At the beginning, I only drew yon-koma. [7] When I came to high school, I offered a magazine to publish my first real story manga. My goal was to get as close as possible to Ryoichi Ikegami's style, even though, eventually, it has nothing to do with him. But the drawing was inspired by him.

The more I drew, the more I included influences, so, progressively, my style slightly changed; but the basis remained Osamu Tezuka's style. Thereafter, it a got mixed with a little bit of Shotaro Ishinomori.

Mangaka Tetsuya Chiba also seems to have impressed you. Could you tell us more about this? [8]

Takahashi: In fact, since I was a child, I've read almost all of Chiba's manga, and I love them. When he radically changed his style with Ashita no Joe, I was surprised. Testuya Chiba's manga don't fade with time. When I was a child, they impressed me, and as an adult, they still impress me. His talent is surprising and I deeply respect him.When did you decide to become a mangaka?

Takahashi: That would have been during spring vacation, between the end of elementary school and the beginning of junior high, that was when I bought a pen for the first time. It's likely at that moment that I considered becoming a mangaka. That was the stuff of dreams; however, I sent the manga I drew to publishing houses. It's only later that I really decided on becoming a mangaka, when I was in my first or second year in university. Strangely, I think that it was the manga I sent in high school that determined my fate. [9]When did you publish your first stories?

Takahashi: Between my second and my third year in university, during spring vacation, I drew a manga that I sent to the New Artist Award and that was chosen. [10] That was how I began. Or rather, that was how I was published for the first time. Luckily, my manga was published in Weekly Shonen Sunday, and things followed on from there. As I was a student, I drew in parallel with my university classes. For Urusei Yatsura, I drew the first five episodes during summer vacation, because the series was planned to stop there. At every summer vacation, I took the opportunity to draw a series of ten episodes one after the other, or short stories for Sunday, for instance. That's how I was left to get organized.At university, I went to class in the morning and I worked on my mangas in the evening, that could be quite demanding. I was entrusted to an editorial manager at Shonen Sunday, and I showed him my cutouts. It was a stimulating period, so I didn't really feel fatigue. He organized himself to avoid impacts on my studies, and I drew tirelessly on week-ends and vacations. Surprisingly, I managed to do it. I didn't need to skip classes, I did go to university. I was never asked for the impossible, the rate of work was reasonable.

How was Urusei Yatsura born?

Takahashi: I attended the classes of Kazuo Koike's Gekiga Sonjuku, and in his classes, one of the exercises consisted in coming up with one new plotline per week. [11] In this way, I gathered a number of storylines that I would later use for Urusei Yatsura. I admired novels by Yasutaka Tsutsui or Kazumasa Hirai, the writer of the Wolf Guy series. [12] As I read further and further, I felt like it would be interesting to blend sci-fi with some elements from the present-day. I told myself, how to say... that it would be interesting to take on, not a manga stroke, but a drawing that's closer to gekiga. [13]In the beginning, I wanted Urusei Yatsura to be sci-fi, a kind of humorous sci-fi series, but when reading letters to the editor, I understood that they were more interested in relationships between characters and I therefore developed that aspect.

As I was barely beginning my career, the series could very well have stopped after five chapters. [14] Surprisingly, the manga got more success than expected. However, I was never told "stop school to draw!". They would rather tell me "draw when you can, but when you draw, draw Urusei Yatsura!"

Once I completed university, I fully devoted myself to manga. Urusei Yatsura thus became a regular series, so it ran smoothly. When Urusei Yatsura became a regular series, I introduced a new character, Mendo, in order to give new dynamics to the story. It was my editor who advised me to insert new characters. The style didn't change much though, since it was at heart a slice-of-life story with alien elements in it. It thus remained Urusei Yatsura.

Urusei Yatsura lasted very long for a first work. What experience did you draw from those 30 volumes? [15]

Takahashi: To be honest, drawing Urusei Yatsura amounted to constant learning. My first editor brought me so much. [16] For example, he insisted that opening scenes were critical; but I couldn't be made aware of it, without that explanation. He also explained to me how you could develop a series' atmosphere while it was ongoing, by letting a new character appear in order to bring another whole dimension. This kind of detail, or even the way he removed panels that were useless to the story, that was daily learning. And over time, I found my own pace. It was a good thing Urusei Yatsura persisted. I think this manga played a major role in developing my mangaka skills.

Before, manga told great epics, like those by Tezuka. But with Urusei Yatsura's success, character-centric manga, which were a minority, started getting fashionable.

Takahashi: For a long time, characters have been important in manga. Gag mangas, like those by Fujio Akatsuka, fully rest on their characters. It's the same for Osamu Tezuka, who developed his "star system". Again, characters are crucial here. There are many other examples out there. Plot is significant, but for me, character reactions may be even more so.Wasn't it daunting to launch a large project like Maison Ikkoku in parallel with Urusei Yatsura?

Takahashi: When Urusei Yatsura's second editor had to move, he asked me if I was interested in a new magazine he was going to launch. [17] By that time, my studies were about to end and in order to become a professional, it was a good thing to accrue work. That's why I accepted. Since it was a seinen magazine, I imagined a manga that would target older readers than those of Urusei Yatsura. I wanted to write a story that took place in a boarding house. I showed some sketches to my editor and he agreed so I went for it. As it was a monthly magazine, in the beginning, the additional workload was not so heavy. After my studies, the magazine went bimonthly, but I kept working at my pace. As the two manga were different, I found some kind of balance. Working on gags made me want to draw a romance like Maison Ikkoku, and vice versa. That was a stressless pace, an enjoyable way to create.How did the idea of this boarding house come to you?

Takahashi: Behind the building where my student room was located, while my career began, there was a strange building, which looked like Ikkoku-kan. A window with broken glasses was letting out piles of books. At the window just above the main entrance, there was often a kendo mask and gloves drying. It was strange! It seems to me it was a student residence. In front of my home, there was a path that linked to an outside road. From that road's end to the inside of the residence, they communicated via walkie-talkies. They could be heard so distinctly that I told myself, "Walkie-talkies are of no use! They do nothing but shout!". It was funny. [18]All of the characters are eccentric. What are your inspirations?

Takahashi: Honestly, there's no model. Those are all characters I completely invented. When I'm asked how I created them, I don't really know how to answer. I felt that kind of people could exist, and I tried to imagine their lives. I was interested in developing their world. It's my way to create characters.That era was full of transition. They aren't rich, but they don't lie at the bottom of the social ladder either. For some, their occupation remains a mystery. Obviously, the wealthy classes don't live in that kind of residence, but this environment is not poor either. In that era, the quality of life was quickly improving in Japan, but I felt this kind of life was still possible. That is how it looked like to me.

Who is your favorite character?

Takahashi: I like all characters. But it's true I especially like the heroine, Kyoko. When I drew her for the first time in a storyboard, I realized she wasn't how I initially imagined her. That is Kyoko! I felt something special, it was strange. When drawing her, I discovered the multiple facets of her personality. She isn't only the ideal girl that's admired by all. She's sometimes temperamental individual. She's a person with her flaws, but these make her even more touching. I wanted readers to perceive her as such, this is what I felt when drawing her. I therefore have a great deal of fondness for this heroine.Why did you choose a widow for a heroine?

Takahashi: I wanted this boarding house manager to be a widow because that situation allowed for many dramatic twists. In my first version, Kyoko thus had a more assertive character, and starting from there, her personality evolved, but her status as a widow remained.Do you give significance to your characters' names?

Takahashi: Names are important. If they don't fit, giving life to characters then becomes very complicated. Because when a name is chosen, it can't be changed again. I'm thus careful when I think about names, so I make no mistake.What did you learn from this first series for young adults?

Takahashi: In the case of Urusei Yatsura, every chapter is independent, and they follow one another in that way. This is also the case in Maison Ikkoku, but compared to Urusei Yatsura, the story is more significant, as well as the characters' daily lives. I really wanted to focus on this aspect when drawing this manga. Understanding the differences between these two stories taught me much. I think shonen manga stands for dreams, while seinen manga is more rooted in reality, or in a daily life without any exaggerations. Even though Ataru, Urusei Yatsura's protagonist, is this way, he has his own ideal and justice. But kicks that make people fly are typical of shonen, along with exaggerated expressions, but for me, they all depict dreams. In comparison, Maison Ikkoku properly describes a real life.With Ranma 1/2, you did a complete change in universe and audience. Why?

Takahashi: For a long time, I had wanted to draw a manga like Ranma 1/2, whose story would take place in a school, with action scenes. I liked Jackie Chan's Drunken Master a lot, and I wanted to draw something like that. I wanted to draw a kind of comedic kung-fu. Then, a character changing genders. Combining both ideas expanded story possibilities, and allowed for drawing different costumes. When the same character can become male or female, drawing gender differences is fun. If he switches genders, even though he keeps the same clothes, as his body's shape changes, his way of wearing them also changes. When I was in junior high or elementary – I don't exactly remember when – mangaka Hikaru Yuzuki used to draw a manga about this topic, and it was very funny. [19]In Ranma 1/2, there is a kind of conspicuous eroticism: you're not afraid to show your characters in all their glory...

Takahashi: There was a novelist who read Ranma 1/2 along with his grandson, and his grandson didn't understand the moments when the character switched genders. If you don't understand that, the story doesn't work anymore. That's why I had to draw it.With hindsight, which scene impressed you, made you laugh or moved you the most in Ranma 1/2?

Takahashi: I like foolish episodes nobody remembers. Overall, drawing Ranma 1/2 really amused me. I especially like the introduction, where I explain how things got the way they are. I think I managed to make those explanations comical. When I manage to set up a basis, characters come alive on their own then. That's how I feel it.Do you always have a clear idea of your series' endings?

Takahashi: I never think about the ending when I start a series. This issue arises only two or three months, maybe six months, before the ending. But otherwise, it's not something I think of when I begin, because it sometimes happens a series goes one more volume than initially intended, its happened once in a while.Why did you go in a new direction to the Inuyasha series?

Takahashi: For Inuyasha, I started with a kind of shonen series I have admired since childhood, those which depict sword fights and yokai, like Dororo (by Osamu Tezuka). But in a recent interview, when I was about to answer, I realized that more than Dororo, it was Hakkenden that had impressed me, Hakkenden meant more for me. [20] It was the kind of adventure I wanted to draw. Until then, I had only drawn comedies. For Inuyasha, I didn't feel the need to draw comedic scenes and so I was relieved. I was delighted to rely on large panels. This led me to think about the page layout. This is really a kind of manga that pleases me a lot, and I was happy to dabble in it.

In the same kind of register, what do you think about Shigeru Mizuki's works?

Takahashi: I own all his books, and I love them. It was Shigeru Mizuki who popularized yokai in Japan. [21] I think that those who, like me, draw yokai today, shouldn't all rely on the same sources. I bore down on drawing yokai Shigeru Mizuki had never evoked. Because in Japan, there are many books about yokai, like anthologies. And of course there are the jigoku ezu, those Buddhist paintings [depicting hell], it was there I found my inspiration.Kyokai no RINNE keeps the Japanese folklore theme but with a lighter tone. What was your ambition?

Takahashi: I came back to a lighter register because Inuyasha was a serious story. Rather than continuing in the same way, I wanted to change. And then, I also like the holidays that are tied to each season. I wanted to do something in that genre again. Reincarnation was not a concept, but rather a starting point. And then I wanted to draw ghosts, with insignificant deaths, unlucky people, nothing too serious. I wanted to come back to a plot you could read without thinking too much about it.Your new series, MAO, has just begun. Can you briefly outline it to us?

MAO's plot plays out during different eras in the history of Japan; the Heian era for the oldest one, the Taisho era that was about one hundred years ago, and the present day. Many events, or rather enigmas, unfold in each era, since it's a manga that cultivates suspense. I'm having fun drawing it. I spread puzzles here and there, but I didn't think much about the follow-up, which means I focus on the mysteries. It's amusing to draw while thinking about the answers I'll then have to find. And since this manga takes place during various time periods, I thus make my aesthetics more diverse, which also pleases me. With all my heart, I would like you to read it. [22]Thank you.

Footnotes

- [1] Kappa (河童) are spirits from Japanese folklore. Rumiko Takahashi's father, Mitsuo, was a gynecologist in Niigata. Her father enjoying drawing and in 1989 she published a collection of his sumi-e paintings of kappa which he published under the pen name Utsugi Takahashi (高橋卯木).

- [2] Rumiko Takahashi has cited these three artists are her earliest influences a number of times in interviews. Obake no Q-Taro (オバケのQ太郎) and Osomatsu-kun (おそ松くん) are classic manga of the 1960s by Fujiko Fujio (藤子不二雄) and Fujio Akatsuka (赤塚藤雄). Osamu Tezuka (手塚治虫) the "God of Manga" is the creator of Astro Boy (鉄腕アトム/Tetsuwan Atomu), Black Jack (ブラック・ジャック) and dozens of other iconic manga.

- [3] Ryoichi Ikegami (池上遼一) is by far Takahashi's biggest influence and favorite artist as she has professed many times. His work includes Crying Freeman (クライング フリーマン), Sanctuary (サンクチュアリ) and Wounded Man (傷追い人). Shinji Mizushima (水島新司) is an artist she has mentioned enjoying, though not to the same extent as Ikegami. Mizushima is known for his baseball manga Dokaben (ドカベン) and Abu-san (あぶさん). Takahashi's speaks of Mizushima in this interview and also here.

- [4] Garo (ガロ) was an alternative, avant-garde manga magazine published from 1964 to 2002. It was fundamental in the development of the gekiga style of manga. It was known for publishing the work of Ryoichi Ikegami (池上遼一), Shigeru Mizuki (水木しげる), Sanpei Shirato (白土三平), Yoshiharu Tsuge (つげ義春) and many others.

- [5] Yoshiharu Tsuge (つげ義春) and Ryoichi Ikegami were both assistants to Shigeru Mizuki and both pillars in Garo. Screw Style (ねじ式/Neji Shiki) is often cited as Tsuge's most influential work. The mangaka Tadao Tsuge (つげ忠男) is his brother.

- [6] Go Nagai (永井潔) is the very versatile mangaka known for Devilman (デビルマン), Cutie Honey (キューティーハニー) and Mazinger Z (マジンガーZ). Go Nagai's Harenchi Gakuen (ハレンチ学園/Shameless School) was highly influential on school set manga and was one of the earliest "ecchi" series. It is thought to be one of the first to feature gags like flipping up girl's skirts and peeping on phyiscal examinations.

- [7] Yon-koma (4コマ) are manga in vertical strips consisting of four-panels.

- [8] Rumiko Takahashi has often spoken of her fondness for Ashita no Joe and its artist Tetsuya Chiba.

- [9] Takahashi mentions in an interview, "I created my first story manga in my second year of high school, and I submitted it to Shonen Magazine. At the time I was a fan of Ikegami-sensei, so I copied his tough/macho style and drew a slapstick gag manga (laughs). It was a slapstick “sword-rattler in which everyone was attacked with biological weapons, and under the setting that no one would die in mediocrity, students and salarymen dueled each other with swords." Other than the plot described here it is unknown what this story was or if it was a reworking of her Star of Empty Trash story. She may not count this as "unpublished" due to it being prior to her debut. If we only count material she has made since 1978 (her debut) then there is nothing that she has ever mentioned that has not been published. However, there are some items that were published and take many years before they are collected in easier to acquire collected volumes such as her yearly short stories.

- [10] Takahashi won honorable mention for the 2nd Shogakukan Newcomers Manga Award (第2回小学館新人コミック大賞) in the shonen category. The way the Newcomer Manga Award is structured is there is a single winner and then two to three honorable mentions that are unranked. In 1978 the winner in the shonen category was Yoshimi Yoshimaro (吉見嘉麿) for D-1 which was published in Shonen Sunday 1978 Vol. 26. The other honorable mentions in addition to Rumiko Takahashi were Masao Kunitoshi (国俊昌生) for The Memoirs of Dr. Watson (ワトソン博士回顧録) which was published in Shonen Sunday 1978 Vol. 27 and Hiroaki Oka (岡広秋) for Confrontation on the Snowy Mountains (雪山の対決) which was published in a special edition of Shonen Sunday (週刊少年サンデー増刊号). Oka would also publish later under the name Jun Hayami (早見純). Other winners in various Newcomers categories include Gosho Aoyama, Koji Kumeta, Yuu Watase, Kazuhiko Shimamoto, Naoki Urasawa, Kazuhiro Fujita and Ryoji Minagawa, Yellow Tanabe and Takashi Iwashige.

- [11] Gekiga Sonjuku was a manga "cram school" where Kazuo Koike, the writer of such iconic manga as Lone Wolf and Cub, Crying Freeman and Lady Snowblood helped train a number of manga luminaries before their debuts. Besides Rumiko Takahashi, other Gekiga Sonjuku alumnai include Tetsuo Hara (Fist of the North Star), Yuji Hori (Dragon Quest), Hideyuki Kikuchi (Vampire Hunter D), Keisuke Itagaki (Grappler Baki) and Marley Caribu (Old Boy).

- [12] Yasutaka Tsutsui (筒井康隆) is a novelist perhaps best known to western audiences as the writer of Paprika which was turned into a film by Satoshi Kon. The Girl Who Lept Through Time (時をかける少女) is another well-known novel by Tsutsui. Kazumasa Hirai (平井和正) was a science fiction novelist best known for 8 Man (8マン), Genma Wars (幻魔大戦) and Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ). Takahashi illustrated a number of his Wolf Guy novels in the early 1980s. He published two interview books of discussions he had with Takahashi entitled The Time We Spoke Endlessly About the Things We Loved (語り尽せ熱愛時代/Kataretsuse netsuai jidai) and The Gentle World of Rumiko Takahashi (高橋留美子の優しい世界/Takahashi Rumiko no Yasashii Sekai) which is his analysis of Maison Ikkoku and Urusei Yatsura Movie 2: Beautiful Dreamer.

- [13] Gekiga (劇画) is a more realistic, less caricatural style of manga.

- [14] Urusei Yatsura's early publication history was fairly non-traditional. After the first five chapters were published weekly from August through September of 1978 the sixth chapter was then published in a special issue of Shonen Sunday in October or November. Takahashi then returned in February to continue Urusei Yatsura for approximately ten chapters. This was because Takahashi was still in college at this point in her life. She then returned to Urusei Yatsura through April 1979 before stopping and publishing the five chapter monthly mini-series Dust Spot!! in a special edition of Shonen Sunday. After Dust Spot!! she returned to Urusei Yatsura sporadically until March of 1980 when its continual, regular weekly publication began in earnest. Looking at the publication dates of the chapters in the first two volumes helps clarify this as well as shows that some of the chapters were rearranged from their original publication order.

- [15] Depending on the country where Takahashi's work is published the number of volumes may vary. Generally speaking Urusei Yatsura was published over the course of 34 volumes in Japan during its publication. It has since been republished in various formats and sizes with the same amount of content condensed into a small number of volumes.

- [16] This would have been Takahashi's first editor, Shinobu Miyake (三宅克). He is the namesake of Shinobu Miyake of Urusei Yatsura fame. In addition to overseeing Urusei Yatsura he also was the editor of Pro-Golfer Saru (プロゴルファー猿) by Fujiko Fujio A (藤子不二雄Ⓐ) and Makoto-chan (まことちゃん) by Kazuo Umezu (楳図かずお).

- [17] The second editor on Urusei Yatsura (and the first editor on Maison Ikkoku) was Takao Yonai (米内孝夫). Takahashi says he is the one that came up with the “Rumic World” term to advertise Urusei Yatsura. The magazine that was being launched was Big Comic Spirits.

- [18] Takahashi would illustrate a short story about the creation of Maison Ikkoku in her work entitled 1980.

- [19] In another interview Takahashi mentions Laugh and Forgive (笑って許して) by Hikaru Yuzuki (弓月光) as being influential in regards to Ranma 1/2. Yuzuki has also made another gender-swap comedy My First Time (ボクの初体験), a shojo manga published in Margaret from 1975-1976. Hiroya Oku (奥浩哉) the mangaka behind Gantz and a noted Rumiko Takahashi fan commented on Twitter about reading Yuzuki's Doron (どろん) and commenting on Takahashi reading his work as well. He also mentioned Takahashi and Laugh and Forgive.

- [20] Nanso Satomi Hakkenden (南総里見八犬伝) is a Japanese epic novel written and published over twenty-eight years (1814–42) in the Edo period, by Kyokutei Bakin. Dororo (どろろ) was Osamu Tezuka's 1967-1969 series about the ronin Hyakkimaru trying to retrieve his missing body parts.

- [21] Takahashi speaks of her love of Shigeru Mizuki's work in this interview. Mizuki is important not only for his manga, but for cataloging the folklore of Japan. Many, if not most, of the yokai that appear in his work are actual yokai passed down through oral tradition in many small towns and villages throughout Japan. Mizuki researched, noted, and illustrated these creatures and spent many years researching and cataloging these stories. Konaki Jijii (子泣きじじい) is a yokai that resembles a baby in size and shape but has the face of an old man. If you make the mistake of picking him up he'll grow heavier and heavier, clinging to you until you are crushed. Sunakake Babaa (砂かけばばあ) is a yokai that sprinkles sand on people that pass under torii gates. Nurikabe (ぬりかべ) is an invisible wall yokai that misdirects travelers and blocks their path. Ittan-momen (一反もめん) is a haunted strip of cloth. Takahashi created a similar creature in Kyokai no RINNE chapter 77. Azuki arai (小豆洗い) are known for the sound of washing beans in a basin, they are typically heard rather than seen, though for the rare person who has ever seen one they are said to look like little old men. Abura-sumashi (油すまし) is a yokai that is said to be the ghost of someone who stole oil, hence their name, "oil presser".

- [22] While filming this interview Takahashi is shown illustrating chapter 31 of MAO.

Stéphane Beaujean interviewed Rumiko Takahashi and is the Artistic Director of the Angoulême Festival.

Translator Antoine Rozier is an English-to-French and German-to-French technical translator. His Linkedin page can be found here.

47th Édition Festival International de la Bande Dessinée d'Angoulême

|