To become a manga artist, you must make the most of your moratorium period as a student.

Translated by: Harley Acres

"Manga artist" may be the most popular profession in Japan right now. But is it possible to become a manga artist after entering college? We asked three representatives of the field to answer this question.Graduated from Meiji University in Manga Studies(?). Now he is aiming to become a man of culture - Jun Ishikawa

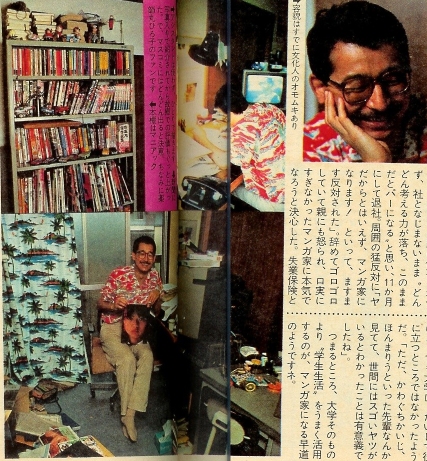

Jun Ishikawa, born in 1951, graduated from the Faculty of Commerce at Meiji University. Though to be exact, he states he is a graduate of the Meiji University Manga Research Institute, "I don't really know what university classes are like." Although he drew manga part-time with the university's manga research club, he still had no intention of becoming a professional and spent most of his time playing mahjong, graduating in five years (it was the era of the lockout, and he was able to graduate by submitting a report). [1]

In his hometown of Toyota City, he joined Toyota with high expectations as a clerk with a college degree, but he soon felt "I don't belong here." After only a month on the job he left the company, thinking "I'm going to lose my ability to think, and if I don't do this, I'm going to go downhill." His parents were extremely angry with him for quitting and hanging around their home so he told them, "I'm going to become a manga artist!" which they were very opposed to, so he decided to seriously try to become a manga artist, which had initially simply been an excuse for him. While eating away at his unemployment insurance and savings, he went around to third-rate magazines and got a few more jobs there. [2] Suddenly, two-and-a-half years and one day later, he received requests from three magazines at the same time: Young Comic (ヤングコミック), Manga Gang (漫画ギャング), and Manga Shonen (マンガ少年), "'What?' I was left thinking, 'I'm still not sure if I'm a manga artist.'" said Ishikawa. Originally a fan of gekiga manga, he has always had a "print nature" and has also branched out into movie reviews, trying to survive as a "human" in the industry. [3] So, it seems that college was not a very useful place for Ishikawa-san either. "However, it was meaningful for me to know that there are great people in the world by watching my seniors such as Kaiji Kawaguchi and Riu Honma," he says. [4]

In short, it seems that the quickest way to become a manga artist is to make the most of your "student life" rather than the university itself.

Straight out of Keio University's Faculty of Economics to become a successful businessman. - Fujihiko Hosono

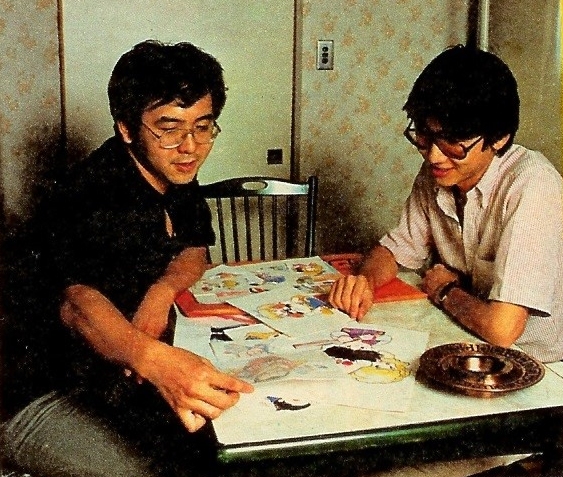

Usually, while on the path to become a manga artist, you either submit work directly to a publisher, win a newcomer award and debut, or work as a professional assistant to hone your skills and bring your work to a publisher (and very rarely through a manga vocational school). In most cases, the period of struggle begins after graduating from high school, but recently the number of manga artists who have graduated from university is increasing. Then, what does university mean to manga artists? I asked Fujihiko Hosono, who just graduated this spring. [5]

Hosono-san was born in 1959. He has loved manga since he was young, and his dream occupation was as a manga artist. When he was in high school, he didn't even submit work to Shonen Sunday (!) or Shonen Jump. He had no options, so he went straight from Keio High School to college. There he joined the science fiction art collective Studio Nue via his friendships in manga and science fiction. As an employee of Studio Nue, he made his debut when he illustrated Crusher Joe by Haruka Takachiho for Manga Shonen. [6] He was amazed at seeing a preview of the magazine and wondered if he was really allowed to appear in such a publication. Later, he was introduced to Shonen Sunday by a friend, and by the time he was in his fourth year, he was already a professional mangaka with two serials in weekly and monthly magazines. Since college was "not directly useful" for manga, he put little effort into the latter half of his studies. In the end, it seems that college was a kind of "back-up option" in case he could not become a manga artist and satisfy his parents. How about the title "brilliant manga artist?" He answered with a laugh, "No, I got a lot of C's on my report card, so I guess I'm a 'C' manga artist."

In order to become a pro as soon as possible, she studied hard and graduated in four years. - Rumiko Takahashi

Born in 1957, Rumiko Takahashi, who is a woman though very active in boys' magazines, graduated from Japan Women's University, Faculty of Letters, Department of History. [7]

When she was in her second year of high school, she contributed to a certain boys' comic magazine, but her submission was rejected. [8] She reluctantly said, "I'll study hard. I want to go to college in a field I'm good at!" In her third year, she made her debut in Shonen Sunday and tried to drop out, but her family objected. Writing her graduation thesis, "Countermeasures for Homeless People," and after serious studying she graduated in four years, believing that the longer she stayed in college, the more it would affect her manga career. [9] The only thing she wanted to be was a manga artist, and now she has actually become one.

When I asked her if college was a waste of time, she said, "No, the books I read in my spare time, the places I went, and the things I talked about with my friends were all useful. I think my college days were used quite effectively... yes." She is quite an intelligent young woman.

Footnotes

- [1] Jun Ishikawa (いしかわじゅん) is a manga artist, though he is much better known as a respected manga critic. He has published two volumes of his collected essays of manga criticism- Manga no Jikan (漫画の時間) and Manga Note (漫画ノート). Takahashi has written about him in her short piece Ishikawa-sensei, Do You Remember?. The "lockout" referred to here is likely associated with the extensive protests in Japan in 1959, 1969 and again in 1970 that are collectively called the "Anpo Protests". We have written more about Ishikawa as well.

- [2] Though it may not have yet been codified when this article was printed in Popeye in 1982, being published in these "third-rate magazines" will become one of the defining characteristics of the "New Wave". The New Wave (ニューウェーブ) movement in manga is a product of the late 1970s into the early 1980s characterized by experimental works that did not fit into the traditional shonen/shojo/seinen/adult manga categories that were established at the time. Small circulation manga magazines such as June (ジュネ), Peke, Boys and Girls Complete Competitive Collection of SF Manga (少年少女SFマンガ競作大全集) and Supplemental Volume of Fantastic Sci-Fi Manga Complete Works (別冊奇想天外SFマンガ大全集) were the homes of these experimental newcomer manga artists. Katsuhiro Otomo (大友克洋) and Hideo Azuma (吾妻ひでお) are both held up as universally agreed upon members of the New Wave, though there is little overall consensus. Other artists often cited as part of the New Wave include Jun Ishikawa (いしかわじゅん), Daijiro Morohoshi (諸星大二郎), Hiroshi Masumura (ますむらひろし), Noma Sabea (さべあのま) and Michio Hisauchi (ひさうちみちお). Though Rumiko Takahashi is not often named as a part of the New Wave, I feel a case could be made to include her. She is of the era and published some small works in Boys and Girls Complete Competitive Collection of SF Manga such as ElFairy/Sprite. The New Wave is said to have ended with the launch of Big Comic Spirits and Young Magazine which served as more mainstream homes for these avant garde artists. Rumiko Takahashi, Hideo Azuma and Jun Ishikawa all were published in the first issues of Big Comic Spirits.

- [3] Indeed this is what Ishikawa will become best known for, perhaps even more than for the manga he creates he becomes a notable manga critic who helps to bring attention to obscure, underground manga. In his collection Manga no Jikan Ishikawa introduced a number of manga series that would be considered "underground" comics. Many of them dealt with motorcycle gangs, gay relationships, little known shojo series and obscure gag strips. The book became a significant hit and established him as a manga tastemaker. Ishikawa is one of the regular panelists on BS Manga Night Talk (BSマンガ夜話/BS Manga Yawa) a manga-focused television program that ran from 1996 until 2009. The show was hosted by folklore specialist Takahiro Ohtsuki (大月隆寛) and the rest of the panel included producer/critic/Gainax founder Toshio Okada (岡田斗司夫) and manga critic/manga artist/grandson of Soseki Natsume, Fusunosuke Natsume (夏目房之介).

- [4] Riu Honma (ほんまりう) was part of the mahjong manga boom in the 1980s with his manga Mahjong Gekitoroku 3/4 (麻雀激闘録3/4). Kaiji Kawaguchi (かわぐちかいじ) is best known for his military manga Silent Service (沈黙の艦隊/Chinboku no Kantai) and Zipang (ジパング).

- [5] Fujihiko Hosono (細野不二彦) is best known for Gu-Gu Ganmo (Gu-Guガンモ), Gallery Fake (ギャラリーフェイク), Sasuga no Sarutobi (さすがの猿飛) and Dokkiri Doctor (どっきりドクター).

- [6] A number of noted manga artists submitted guest character/alien designs for the Crusher Joe film including Rumiko Takahashi.

- [7] Takahashi graduated from Japan Women's University (日本女子大学/Nihon Joshi Daigaku) in 1980 after her 1978 debut in Shonen Sunday. As a result of trying to work as a fulltime, professional mangaka while attending school Takahashi's early work on Urusei Yatsura was sporadic until 1980.

- [8] Takahashi has spoken about this in a few interviews. She submitted a story to Shonen Magazine thought it has always been unclear what the nature of this story was. She states that she did this because her idol, Ryoichi Ikegami, was publishing in Shonen Magazine at the time. Ironically he would soon leave the Kodansha publication and spend most of the rest of his career at Shogakukan, even publishing alongside Takahashi in Shonen Sunday in the 1980s.

- [9] Popeye abbreviates her thesis to simply state it is "Countermeasures for Homeless People" (無宿人対策), however the full title is "The Edo Shogunate's Countermeasures Against Homeless People" (江戸幕府の無宿人対策). Takahashi's discusses her thesis in "Gekkan Takarajima" (February 1982) (月刊宝島」1982年2月号) which was later collected in "Manga-ka ga Tsutaeru" (Manga Critique Compendium, Vol. 4: Heibonsha, 1988) (マンガ批評大系第4巻:平凡社、1988年).

- [10] It may seem a bit odd for Takahashi's relationship status to be listed here, however Popeye is a men's fashion magazine, and Takahashi was still at the very beginning of her career when this piece was written. Popeye, "the magazine for city boys," is still an important magazine in Japan for introducing "Ametora" (American traditional) fashion to Japan which includes Levi's 501 jeans, Red Wing boots, and Ralph Lauren polo shirts. Two excellent articles on the history of Popeye are A Halcyon Existence: The Legacy and Longevity of “Popeye” Magazine and How Japan Beat America At Its Own Style Game.

ポパイ 1982年9/10

|